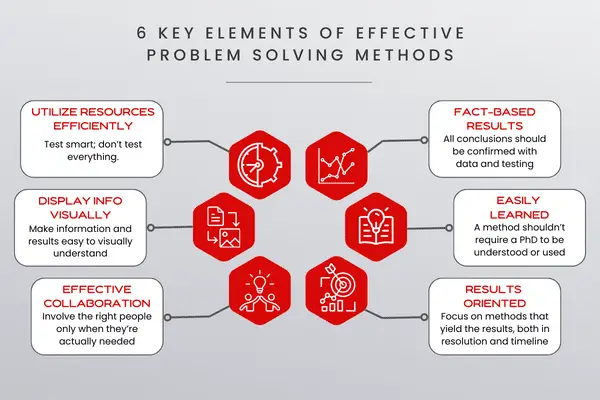

There have been many articles written about the important steps in a problem-solving method: Clearly define the problem, Evaluate the measurement system, etc. Because of this, nearly every problem-solving framework you come across will contain these same steps. And when there are such similarities, it can often be difficult to distinguish what makes one method better than another. In this article, I want to look at the process differently. With over 29 years of experience in solving technical problems, I’ve come to discover another set of differentiating factors that make a problem-solving method effective. In my experience, the key elements of an effective problem-solving process are:

- Promotes Effective Collaboration

- Visually Displayed Information

- Efficient Resource Utilization

- Fact Based Analysis

- Easily Learned

- Achieves Results

That said, let’s look at each.

Promotes Effective Collaboration

An effective problem-solving method enables collaboration between different team members, from different sites and with different skills. This means people from various parts of the organization can help collect critical information, give their interpretation of what it means, and offer ideas of what may be happening. It is the opposite of an individual scouring a large database yelling, “Eureka!” when they think they have found the answer.

Some people may misinterpret the need for collaboration to mean you need a large team of people for problem solving, but this is not the case. As teams get larger, making decisions and moving forward becomes more difficult, so it is important to keep the core team small and collaborate with others on an as-needed basis.

For example, an hourly operator not on the core team might recognize a certain defect pattern as matching something in the process when that information is displayed the right way. Not everyone will recognize a pattern in hundreds of rows in a spreadsheet, but they may be able to find a matching pattern if you tell them it happens on every 5th part when they know they change a hand tool every 5th part. This need to have information displayed in the right way leads directly to the next essential element.

Key Takeaway

The problem-solving method should encourage keeping the core team small but allow and encourage them to call on important resources as needed while not allowing them to exclude pertinent resources.

Visually Displayed Information

Good visual display of measurements and test results leads to more effective communication, so how we display information should be well thought out and deliberate. When solving technical problems, we often need to communicate results and information with multiple levels of people.

The measurements and results should be easily understood by everyone from the hourly operator to the technical subject expert, to the executive leader in the report out. It should be displayed in a way that is easily understood by all stakeholders.

For effective collaboration, structuring information in a way that matches our physical processes and part designs enables teams to be better able to see patterns and recognize potential sources of those patterns. Sometimes the best insight into difficult problems comes from having a simplified visual of the issue and where/how it’s occurring. And while many software packages can generate beautiful output graphs; most are not structured in the best way to make pattern recognition easy.

Key Takeaway

The method should make progress & results easy to understand visually. Not everyone will have time to read the full report. Make it visual.

Efficient with Resources

A trial-and-error approach that is not getting you closer to the source of your problem is not an efficient use of your resources. When resources and time are an issue, a good problem-solving method can get the most information out of the fewest number of measurements, with the fewest number of parts, and the fewest number of tests. The challenge is to figure out which ones to leave out and which ones to include. Being more efficient allows your organization to solve more problems faster with existing resources.

Key Takeaway

Use problem solving methods that don’t require exhaustive data collection.

Fact-Based Analysis

Over the years, I’ve encountered my fair share of unique problems, including some that presented with typical failure modes but ended up being the result of some hidden and complex technical cause. And in these cases, the problem has persisted despite the concentrated efforts of the problem-solving team.

When reviewing those efforts, I’ve often seen an extended hyperfocus on a specific potential cause, identified by opinion or guess, even when the data didn’t support it.

Our problem-solving training courses always elicit a few stories from attendees about how “people run down their first guess continuously” without regard to the data and the problem persists.

When considering a problem-solving method to add to your toolbox, examine if the method prioritizes gathering facts and displaying them to enable pattern recognition. Patterns help get us closer to the root cause of a problem. In other words, the method should prioritize facts over opinions and be structured to enable pattern recognition quickly.

Avoid selecting methods that enable guesses and conjecture when trying to identify the source of a problem. Brainstorming is a good technique to develop creative solutions once a root cause has been identified but should be avoided as a technique for “finding the root cause”.

Key Takeaway

Select problem solving methods structured to support data-based decisions and limit hypothesizing.

Easily Learned

When adding a new problem-solving method to your company’s toolbox, you want to be sure that it can be used by many, not just a select few. Good problem-solving methods do not require a PhD to become proficient. If the method you’re considering can’t be taught to most of your team, your whole team can’t be part of your problem-solving culture.

The most effective problem-solving organizations I’ve seen have a problem-solving culture that touches every person employed there: from the CEO to the hourly operator. Everyone has some level of understanding of how best to solve problems.

And they’re aligned.

That’s the key. They’ve selected problem solving methods that make it easy for anyone in their organization to learn, implement, and communicate about their problems.

Key Takeaway

Choose a method that your entire team can learn, use, and understand.

Achieves Results

Ultimately, the success of your problem-solving method is measured by your results. And while every method will demonstrate some success, you should look deeper than the surface.

The output of effective problem-solving methods is not a science project which ends with a report or a white paper with no change in performance. Rather, a successful problem-solving method results in changes being implemented that improve your business metrics in a reasonable amount of time.

When vetting a problem-solving method, consider not only that the issues get resolved but also how long it takes for that resolution to happen. After all, time…and more defects…cost money.

Key Takeaway

Trust but verify the stated results of a method. Look for not only root cause resolution but also how long that takes.

Problems abound but solutions do, too

Every company has problems, and every company can benefit from a good problem-solving method. Regardless of what you build or sell, implementing an easily learned, results oriented problem-solving method that includes effective collaboration, visually displayed information, efficient resource utilization, and fact-based analysis will yield better results to your bottom line faster.

About the Author

EXECUTIVE VP - PROBLEM SOLVING

John Abrahamian

John Abrahamian is a highly respected problem solver and an expert in Lean manufacturing, with a career spanning over three decades. Throughout his career, John has become renowned for his innovative problem-solving approach and unwavering dedication to customer satisfaction. His experience in various industries, including aerospace, automotive, medical devices, and consumer products, positions him to effectively guide cross-functional teams through manufacturing and engineering challenges. He holds a Bachelor of Science in mechanical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a Master of Business Administration from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.